Balanchine: The City Center Years

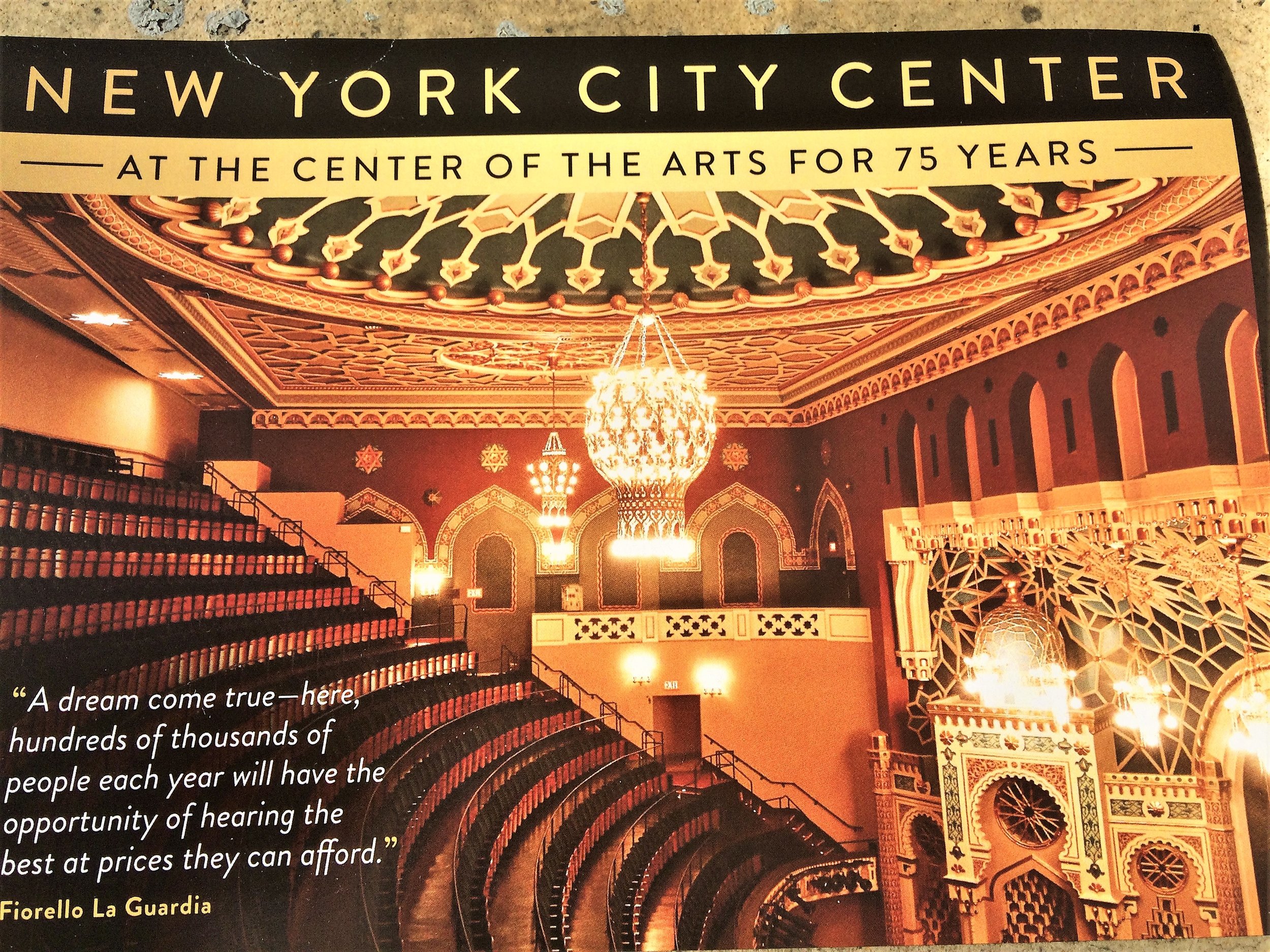

When Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia opened the doors of New York City Center in 1943, he was fulfilling a promise to New Yorkers that they could see world-class performances at affordable prices. It was all part of a plan to make New York the center of innovation in the worlds of dance, music, and theater. It was a promise made, a promise kept.

Within a few years, by 1948, George Balanchine (1904-1983) and Lincoln Kirsten founded the New York City Ballet and it became the resident company at City Center. It would remain there until 1964 before moving to a larger theater designed, in part, by Balanchine at Lincoln Center.

But it was New York City Center that provided Balanchine with his first artistic home in the United States, and it was on their stage and in their studios that Balanchine’s neoclassical style came to fruition. According to PLAYBILL, money was sparse for the young troupe, so rehearsal clothes and simple leotards often took the place of the more elaborate costumes and sets belonging to classical ballets such as “Swan Lake” and “Giselle.” This pared down approach became a signature of the American Modernism that Balanchine created. But I confess that seeing the same blue background for each and every one of the ballets left me hungry for the ‘extras.’

To celebrate its 75th Anniversary, City Center scheduled a glittering festival of events including “Balanchine: The City Center Years.” To honor the maestro properly, eight ballet companies participated, including the Paris Opera Ballet, the Mariinsky from Russia, and the Royal Ballet from England. Also on board were New York City Ballet; Miami City Ballet, an offshoot of New York City Ballet; San Francisco Ballet; the Joffrey Ballet; and the American Ballet Theater. I arrived early, with plenty of time to grab a coffee at Markato, next door, and snag a table with a good view of all those New Yorkers going by on West 55th Street.

Of course, Desperately Seeking Paris, wanted to see the Paris Ballet perform, so I attended the matinée performance Saturday November 3rd in which the exquisite premier danseur Sae-Eun Park was partnered by the principal dancer Hugo Marchand (left, taking a bow) in the pas de deux from Agon. Music by Igor Stravinsky—the other maestro!

The performance was ravishing, even when seen from the next-to-the-last row in the orchestra. One of the glories of City Center, versus Lincoln Center, is that the dancers are closer to the audience and the stage is smaller, so when a company appears in a finale, they really fill the stage. As I sat watching, there was this dawning awareness that so many of the male dancers were short, especially compared to Marchand, who filled the stage with his great height (6’ 2”) and leaps, thereby highlighting the beauty and delicacy of Sae-Eun Park. (To see him leap and hover, click here.) He was magnificent to watch. Only then did I fully understand Balanchine’s preference for tall dancers, but wondered if there was ideal male or female body for ballet? I think talent will out, no matter what, but when dancing at the elite level it’s best to be tall and slim. And strong.

It has been said that what pointe is for girls, pas de deux is for boys. Lifting is an essential part of the schooling, and a lift can go wrong in a second, doing serious damage to a young man’s back. You’ve got to be strong! And you must be assigned the correct roles, depending upon your strength and body type. And of course, light and lithe ballerinas are easier to lift.

Suzanne Farrell, Balanchine’s muse and widely thought to be the foremost American ballerina of the ‘60s and ‘70s, comes to mind: At 5’7’’ she was slightly taller than the average ballerina, slim, and with those graceful leg extensions and the elegant elongated neck (you look taller!) she dominated the stage and thrilled audiences. Tall is good for ballet, but there was a time when it was thought ballerinas should be short. The fashions change.

The interracial pas de deux from Agon—a mix of intimacy and sensuality—when originally danced by Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams in 1957, caused a sensation, as Mitchell was the first African-American dancer to join New York City Ballet and Adams was white. Sixty years later, seeing Marchand and Park dance the pas de deux was sensational, but for all the other reasons.

Apologies mes amies for the poor photos of the dancers, but in bopping around town, I rely on my iPhone camera, and while it’s ultimately convenient, it’s not all that great for distance shots.

It was so good to be back at City Center for this momentous occasion. It brought back so many happy memories. The beautiful Moorish theater, itself, is haunted by the ghosts of those who have performed there, and in a room off to one side I found twenty-plus framed drawings by Al Hirschfeld. The one to the left, done in 1949, has George Bernard Shaw manipulating Frances Rowe and Maurice Evans in Shaw’s “The Devil’s Disciple” which opened at City Center and later moved to Broadway, becoming the first play at City Center to make the transfer.

What’s more, City Center is capturing a singular piece of theater history, unveiling a new staging of A Chorus Line as part of it’s 75th Anniversary Celebration. When A Chorus Line opened in 1975 on Broadway, the Great White Way was in serious trouble, attendance down, the lights going out. This year they had record attendance and a billion dollars in receipts!

That’s all for today, guys and gals! May all the joys of Thanksgiving be yours…easy on that pumpkin pie! Hope to see you back here in December when I’ll have the coffee ready. Until then, thanks for coming by…À bientôt j'espère